Footprints

As published in CompassSport Magazine recently.

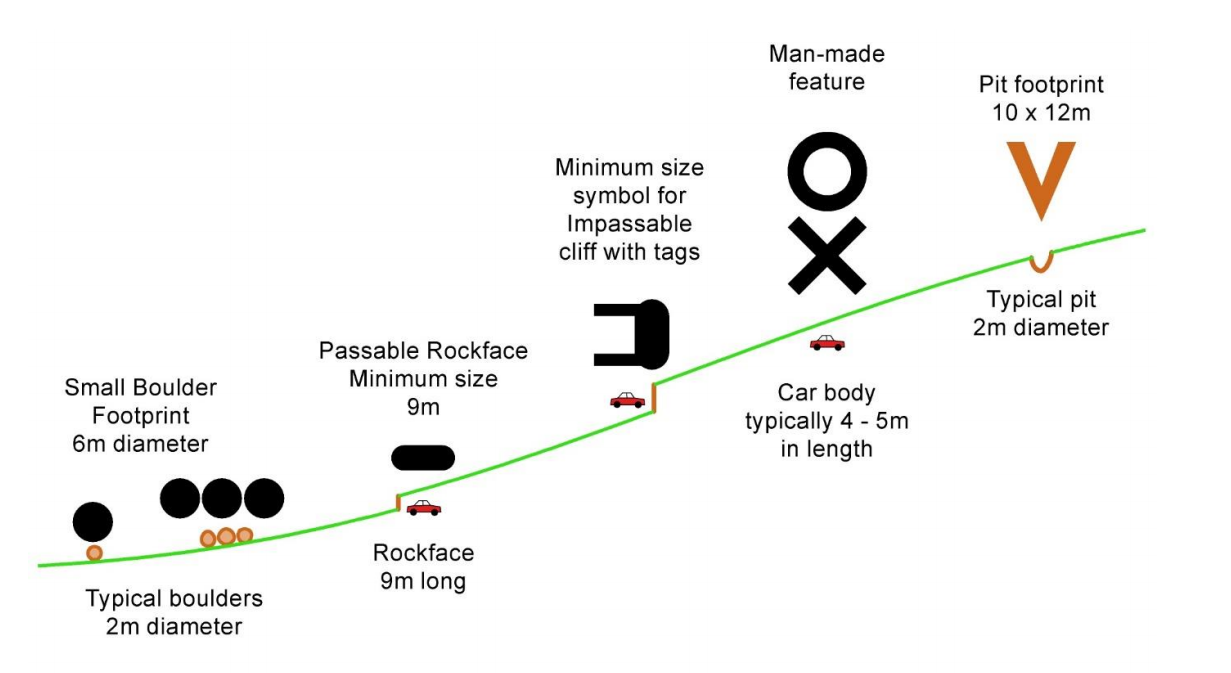

In order for maps to be legible, it’s natural that some symbols on the map have a bigger ‘footprint’ than the objects they represent on the ground. For example, a boulder on a forest map, 0.4mm at 1:15,000, has a footprint of 6 metres, but when was the last time you saw a boulder 6 metres wide? For an isolated boulder this doesn’t cause any difficulties for the mapper, but multiple boulders in a detailed area can quickly become problematic. For two boulders, ISOM stipulates a minimum gap between them of 2.25m (0.15mm at 1:15,000), so now from edge to edge the combined symbol is now 6 + 2.25 + 6 = 14.25m, compared to perhaps 3m on the ground if two 1m boulders are separated by 1m. It can be useful to think of everyday objects, such as a 4-5m long car, to visualise some of these sizes.

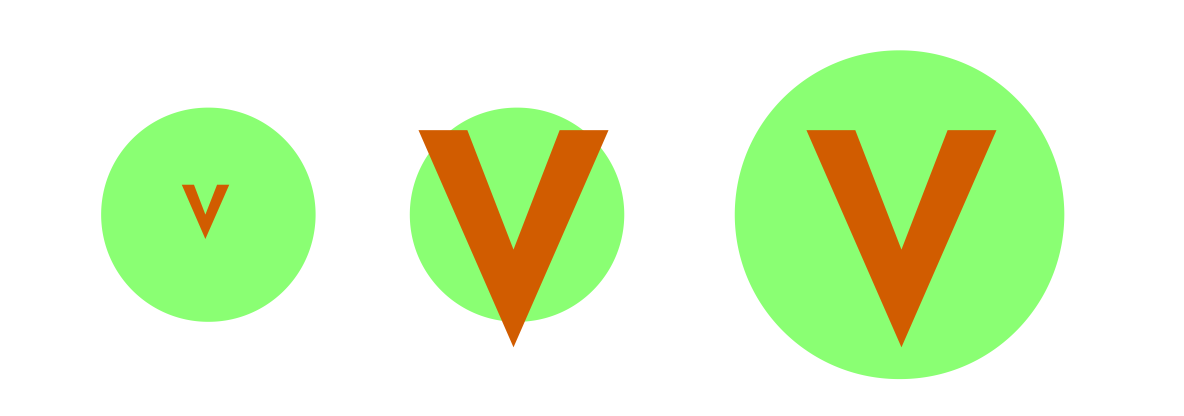

This is, of course, completely necessary and natural - if boulders were half their size on the map you wouldn’t see them - and happens on all maps. A trig point symbol on an OS 1:25,000 map has a footprint of about 20 metres. However, the interplay between some of the vastly enlarged symbols and some of the more true to size symbols is something the mapper needs to think about. For example, think of a pit in a patch of medium green. In reality, this pit is about 3 metres wide and the thicket is about 12 metres wide. The left-hand diagram shows this. The thicket can be mapped true to size and still be ISOM compliant, but the ISOM pit symbol has a footprint of about 10 x 12m! So we get the central diagram. Now, this is ISOM compliant, but does it accurately represent the ground? Perhaps it would better represent the ground if the mapper enlarged the thicket a little, to show that it fully encloses the pit - something like the right-hand diagram. Of course, you have to be careful because now the runner may be expecting a slightly bigger thicket than it actually is. However, given what we have said about other symbols being enlarged, I would argue that this should still feel natural to the runner.

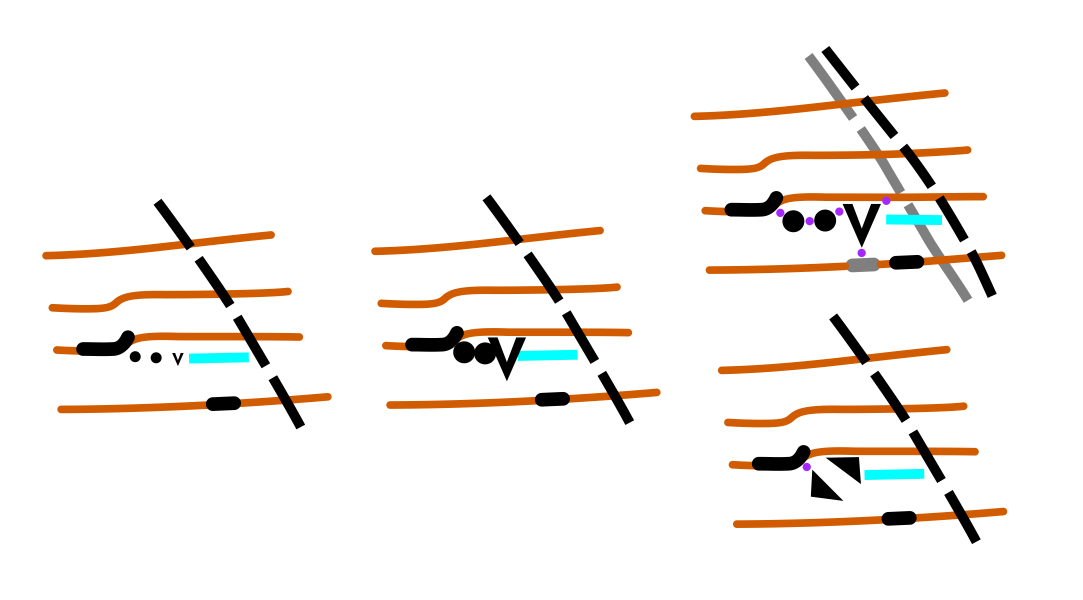

Similar scenarios also exist for the relative positioning of things. In the next example, we have some rock detail on a slope. Again, the left-hand picture shows the ‘true picture’ on the ground. The stream is more just to keep track of the distance between the pit and the path. Note also the small crag is SE of the pit. Using the correct size ISOM symbols, we see the central picture where multiple minimum gaps have been violated. For a runner, they would likely just see a mush of black, unable to pick out “crag, boulder, boulder, pit”.

Now, the usual course of action for the mapper here is to move towards the upper right-hand picture. The crag, boulder, boulder and pit have been separated to be ISOM compliant (shown by purple dots), but this has distorted the meaning of the map! The true positions of the path and the smaller crag are shown in grey, and we can see the small crag has become due south of the pit, and the pit now appears immediately adjacent to the path. So, despite already being ISOM compliant, we should shift the path and small crag slightly too to maintain better relative positions to the rock detail. Of course, the small crag is now a different (and incorrect) bearing from the larger crag, but it is a much smaller discrepancy. The relative positions to the closest features matter the most. If this snippet exists in an otherwise vague area, we don’t have a problem, the distortions are either not noticeable or we can gradual iron them out. Perhaps we just gradually bring the path back towards it’s true position to the north and south, as imperceptibly as we can, as any corners don’t exist on the ground.

However, the mapper has other options. Perhaps there is a lot of other detail nearby and they don’t feel they can distort the position of the path by ~8m. Taking another look at the area, maybe the boulders are small, there are a few other rocks nearby, and the rocky pit could also pass as a jumble of boulders. Maybe the mapper can decide to generalise to a small boulder field, which they can fit into the space available without needing to move the path or the smaller crag.

It is decisions like these that mappers confront all the time - small distortions and clever choices that hopefully lead to accurate and legible maps, as is always the goal.